Related Articles

Federal Judges Order Trump Administration to Fund Food Aid Amid Government Shutdown

UN Security Council Affirms Morocco's Autonomy Plan as "Most Feasible Solution" for Western Sahara Dispute

In a pivotal legal outcome that underscores the complex interplay between climate activism, heritage protection, and civil liberties, three environmental campaigners have been cleared of charges following a high-profile protest at Stonehenge. The decision by a Salisbury Crown Court jury has reignited debates surrounding the boundaries of peaceful demonstration and the application of contemporary protest laws in the United Kingdom.

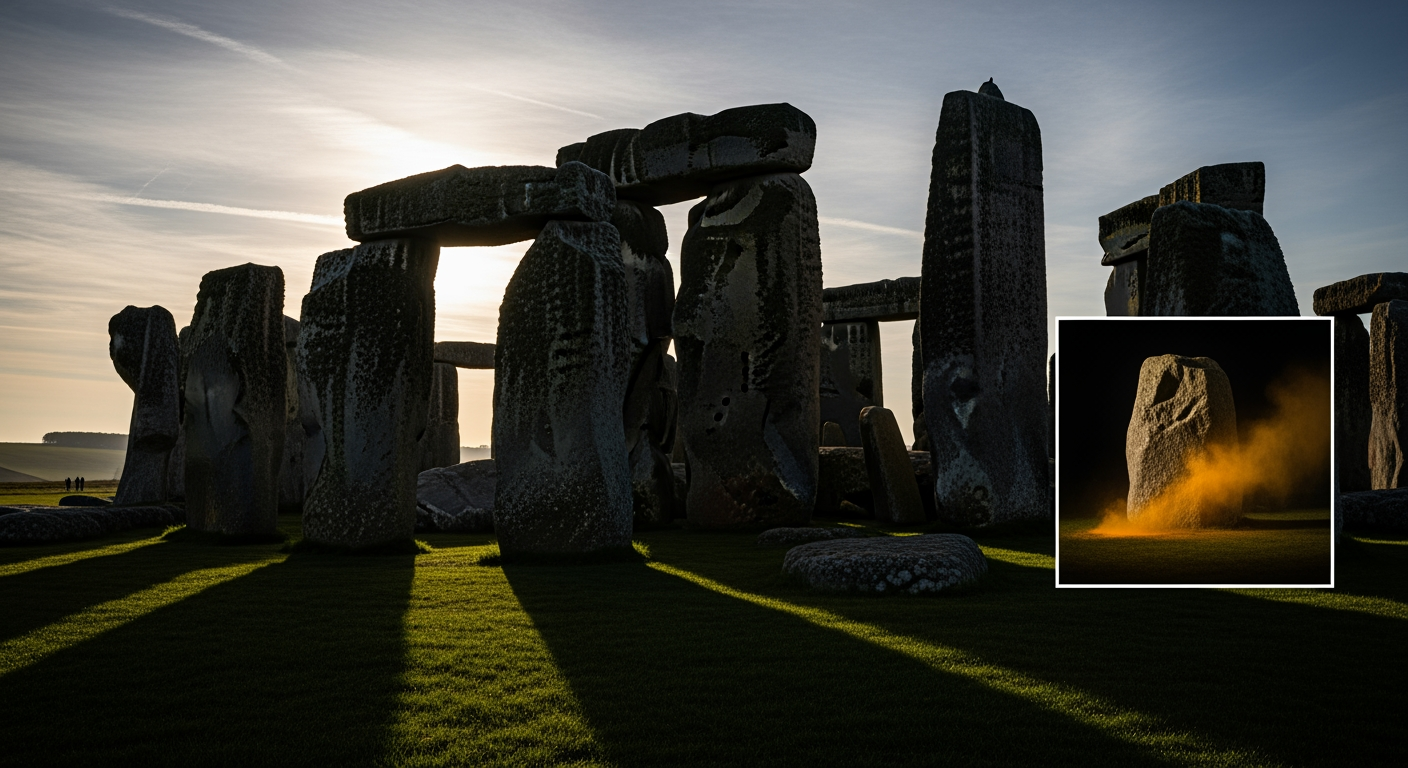

The incident, which occurred on June 19, 2024, saw activists Rajan Naidu, Niamh Lynch, and Luke Watson target the prehistoric monument with orange powder, a day before thousands were expected to gather for the summer solstice. The trio, affiliated with the Just Stop Oil campaign group, stated their actions were a stark call for the incoming UK government to commit to a legally binding treaty to phase out fossil fuels by 2030, emphasizing the urgency of the climate emergency. Their acquittal, following a 10-day trial, marks a significant moment for protest movements operating under increasingly scrutinized legislation.

The protest unfolded dramatically as Naidu, 74, Lynch, 23, and Watson, 36, approached the globally recognized UNESCO World Heritage Site. Using "colour blasters" filled with orange cornflour, talc, and synthetic dye, Naidu and Lynch sprayed several of the ancient sarsen stones, creating a vivid, albeit temporary, orange hue across parts of the monument. Luke Watson was identified as having procured the equipment and driven his co-accused to the site.

Bystanders at the site reacted immediately, with some attempting to physically intervene and halt the spraying. Images and videos of the protest quickly circulated globally, drawing widespread condemnation from political leaders. Then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak swiftly decried the act as a "disgraceful act of vandalism," while opposition leader Keir Starmer labeled Just Stop Oil "pathetic" and insisted those responsible should face the "full force of the law."

Despite the immediate outcry, Just Stop Oil maintained that the orange powder was harmless, made from cornflour and designed to wash away with rain, leaving no lasting damage. English Heritage, the charity responsible for managing Stonehenge, confirmed that the powder was successfully removed shortly after the incident at a cost of £620, expressing initial concern for the rare lichens growing on the stones. However, their subsequent assessment reported "no visible damage."

The three activists were subsequently charged with two offenses: damaging an ancient protected monument and causing a public nuisance. The latter charge falls under the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022, a controversial piece of legislation that has drawn criticism for potentially curtailing the right to protest by introducing broad powers for police to manage and restrict demonstrations.

During the 10-day trial at Salisbury Crown Court, the prosecution presented the protest as a "blatant and clear vandalism," arguing that the specific location of Stonehenge had no direct connection to the climate emergency, and therefore the protest did not necessitate interfering with such a significant cultural landmark. They emphasized the global importance of the 5,000-year-old monument as a site of education and spiritual experience, visited by millions annually.

The defense, however, centered its argument on the fundamental human rights to freedom of expression and protest, citing Articles 10 and 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The activists contended that their action was a peaceful protest, carefully planned to avoid permanent damage, and was a "reasonable excuse" given the existential threat of climate change. Judge Paul Dugdale, in his summing up, instructed the jury to consider whether a conviction would constitute a "proportionate interference" with the defendants' human rights, acknowledging the inherent tension between the right to protest and the protection of a world heritage site.

After several hours of deliberation, the jury returned not guilty verdicts for all three activists on both counts. The decision was met with relief by the defendants and their legal team, who asserted that the public nuisance charge should never have been brought, viewing it as an "affront to their right to protest." Following the acquittal, Rajan Naidu articulated his belief that the judicial system must "wake up" and defend against "climate criminals," reiterating the call for a global Fossil Fuel Non-proliferation Treaty. Niamh Lynch emphasized her motivation, stating, "If you see something you love being hurt, you do everything you can to help. It's quite simple. It's totally natural."

This verdict is poised to have significant implications for the landscape of protest and activism in the UK. It highlights the judiciary's role in balancing the state's interest in maintaining public order and protecting property with individuals' rights to voice dissent, particularly on issues of profound public concern like climate change. The outcome suggests that while disruptive, protests carefully calibrated to minimize lasting damage and rooted in a compelling public interest argument may find legal protection under human rights frameworks. The ruling could serve as a precedent, influencing future prosecutions under the contentious Public Order Act and potentially empowering climate activists to continue using high-profile, non-violent direct action to draw attention to their cause.

Stonehenge, a monument steeped in 5,000 years of history and mystery, has often served as a backdrop for various forms of public expression, though none recently have garnered such intense global scrutiny. Its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site underscores its unparalleled cultural and historical value, making it a powerful symbol. Just Stop Oil’s selection of Stonehenge was deliberate, aimed at generating "maximum impact" by juxtaposing the ancient, enduring stones with the perceived fragility of human civilization in the face of climate change.

The choice of such an iconic and sensitive location inevitably sparks strong public reactions, dividing opinion between those who support the activists' underlying message and those who condemn the targeting of historical treasures. While the immediate focus was on the orange powder, the broader implication of the protest, amplified by the trial, has been to draw renewed attention to the climate crisis and the tactics employed by environmental groups.

The case of the Stonehenge activists serves as a potent reminder of the ongoing tension between preserving national heritage, facilitating peaceful protest, and addressing urgent global challenges. The jury's decision has, for now, tilted the balance in favor of the right to protest, sending a clear message about the limits of criminalizing actions that, while disruptive, are deemed a proportionate exercise of fundamental freedoms. The outcome will undoubtedly be closely watched by legal experts, activists, and policymakers as the UK navigates the evolving landscape of public demonstration in an era of heightened social and environmental awareness.