COP30 Concludes in Uneasy Compromise, Sidestepping Fossil Fuel Phase-Out Amid Global Divisions

BELEM, Brazil – The 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) concluded in Belem, Brazil, after two weeks of intense negotiations, leaving a significant void in its final agreement: a clear commitment to phase out fossil fuels. The summit, which ran into overtime, delivered a deal that calls for renewed global efforts to combat rising temperatures and boosts climate finance for developing nations, but conspicuously omitted direct language on transitioning away from oil, gas, and coal. This outcome underscores deep, persistent rifts among nations regarding the future of climate action and has been met with both cautious approval and profound disappointment from delegates worldwide.

A Summit Defined by Division in the Amazon

COP30 convened in the Amazonian city of Belem, Brazil, carrying the weight of urgent global expectations to accelerate climate action. From its outset, the conference was marked by high stakes and fundamental disagreements, setting a contentious tone for the two-week period. The significance of the location, amidst the world's largest rainforest, served as a stark backdrop to the ecological crisis under discussion. Notably, the United States, a major historical emitter, declined to send an official delegation, further complicating the multilateral efforts. Inside the negotiating halls, discussions were often fraught, with delegates grappling with the delicate balance between economic development and environmental imperative. Outside, the conference faced visible public pressure, as indigenous activists notably stormed the entrance at one point, demanding accountability and highlighting the immediate human interest element of climate change in their communities. This contrasted sharply with the presence of fossil fuel lobbyists within the conference, creating a palpable tension between competing visions for the planet's future.

The Unresolved Core: The Future of Fossil Fuels

At the heart of COP30's contentious negotiations was the undeniable issue of fossil fuels. A large coalition of more than 80 nations, including the European Union, the United Kingdom, Colombia, Panama, Uruguay, France, and Spain, arrived in Belem with a unified and ambitious agenda: to secure robust language for a rapid phase-out of oil, coal, and gas. These countries emphasized the scientific consensus that fossil fuels are the primary drivers of global warming and essential for limiting temperature rises to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Colombia, a particularly outspoken advocate, underlined that fossil fuels are by far the biggest contributor to planet-warming emissions, and its negotiator declared that the country could not support any deal that ignored scientific realities. Colombian Minister of Environment Irene Velez accused the summit of failing its core mission, while President Gustavo Petro voiced his opposition to the final document, stating it did not clearly acknowledge fossil fuels as the cause of the climate crisis.

In direct opposition stood a powerful bloc of major oil-producing nations and some emerging economies, notably including the Arab Group led by Saudi Arabia. This group firmly resisted any explicit mention of a fossil fuel phase-out, asserting their sovereign right to utilize these resources for economic growth and development. The deep chasm between these two perspectives created an impasse that dominated much of the summit's duration, forcing negotiations into overnight sessions as the official deadline passed.

Tumult and Tense Negotiations Mark the Final Hours

The final days of COP30 were characterized by escalating tension and a scramble for compromise. Negotiations stretched beyond their scheduled Friday deadline, spilling into Saturday, a testament to the difficulty in bridging fundamental differences. Tense overnight discussions, particularly between the European Union and the Arab Group, highlighted the deep divisions surrounding fossil fuels. On the plenary floor, frustrations boiled over, with delegations from the EU, Colombia, Panama, and Switzerland openly protesting the draft agreement by raising flags and voicing their objections to the absence of strong fossil fuel commitments.

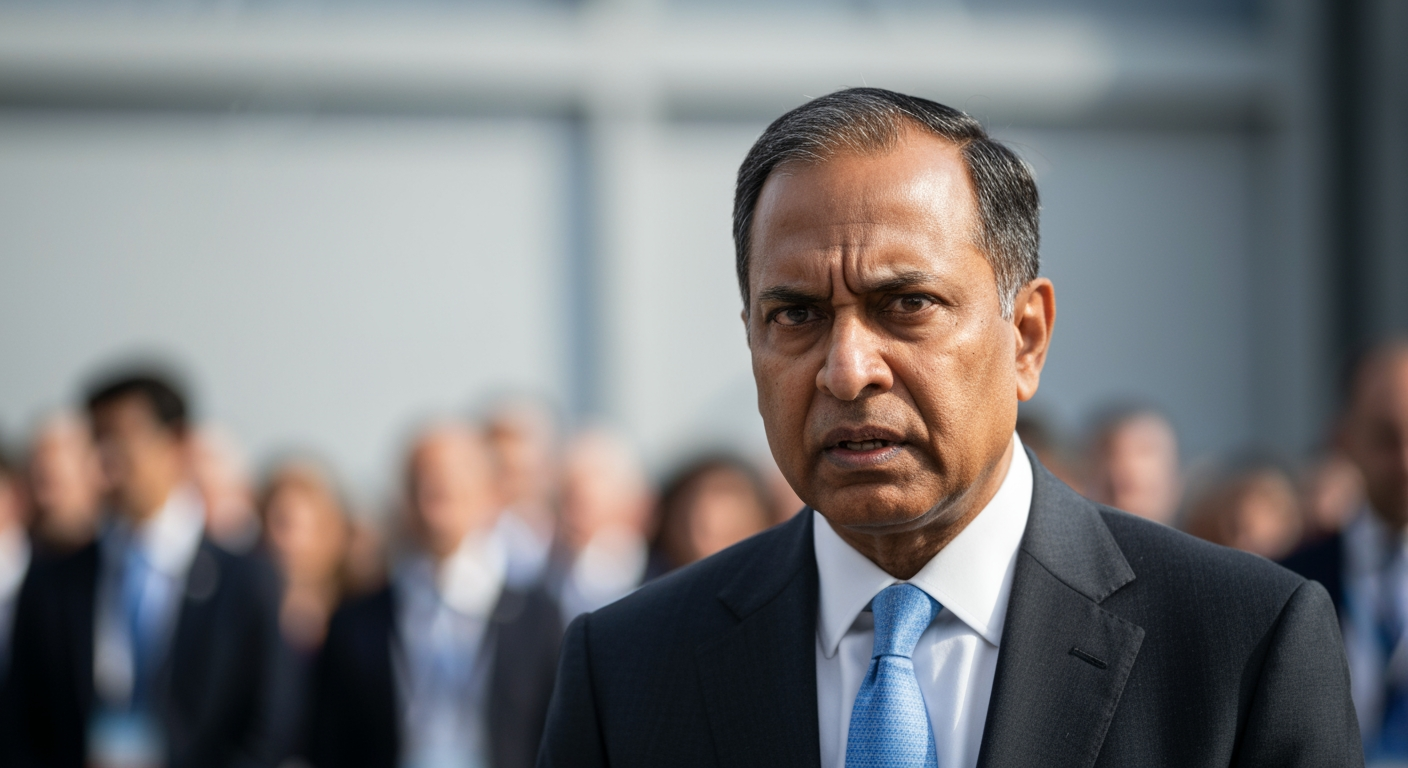

Andre Correa do Lago, the Brazilian COP30 President, found himself in a challenging position, tasked with steering the complex discussions towards a palatable outcome. He temporarily suspended the plenary session amid the protests, acknowledging that many delegates harbored greater ambitions for the summit's conclusions. Upon resuming, he confirmed the approval of the texts despite the significant objections, and issued a "side text" on fossil fuels and forest protection, indicating that these crucial issues were kept out of the main accord due to a lack of consensus. This move, while securing an agreement, underscored the ongoing inability to forge a unified stance on these critical climate drivers.

Compromise and Lingering Frustration on the Path Forward

Despite the failure to secure a direct fossil fuel phase-out, COP30 did yield some progress in other areas. The final agreement included a boost in finance for vulnerable nations grappling with the impacts of global warming. Specifically, a new goal was established to triple climate finance to $120 billion annually by 2035, aimed at assisting developing countries in adapting to and addressing climate change impacts. Additionally, the conference saw the adoption of the BM action mechanism, an initiative designed to ensure the just, fair, and equitable inclusion of developing countries in the burgeoning renewable energy economy.

However, these gains were overshadowed for many by the critical omission regarding fossil fuels. The final text committed nations only to accelerating climate action on a "voluntary" basis, a weaker stance than many had sought. European Commissioner for Climate Action Wopke Hoekstra summarized the widespread sentiment, stating that while the EU would support the agreed-upon text, "we would have liked to see much more, especially more ambition." Despite the controversy, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula Da Silva hailed the summit as a success, asserting that "science prevailed, multilateralism won" at COP30. Yet, the uneasy compromise leaves a tangible sense of frustration, indicating that the global community remains deeply divided on the most critical aspect of climate mitigation.

An Uneasy Path Forward

The conclusion of COP30 without a definitive fossil fuel phase-out clause signals a challenging road ahead for global climate action. The outcome reflects the complex interplay of national economic interests, differing levels of development, and the urgent scientific mandate for change. While the increase in climate finance and the focus on equitable transitions offer some forward momentum, the fundamental challenge of weaning the world off fossil fuels remains largely unaddressed in a binding, collective manner.

The implications of Belem's outcome are significant. It demonstrates the continued difficulty in achieving consensus on the most impactful climate policies, particularly when they impinge on the economic models of powerful nations. As the world looks ahead to COP31 in Turkey, the divisions exposed in Brazil will undoubtedly continue to shape future negotiations. The UN climate secretariat's head, Simon Stiell, acknowledged the frustration but praised delegates for coming together in a year marked by denial and division, encapsulating the fragile hope that persists amidst the setbacks. An advisory opinion from the UN's top court, rendered earlier this year, stating that parties are obliged to follow agreements reached at COP conferences, adds a layer of moral, if not always immediate legal, pressure on future commitments, especially against the backdrop of significant global political shifts concerning climate policy. The uneasy compromise reached at COP30 underscores that the fight against climate change is far from over, and indeed, the most difficult battles may still lie ahead.